Without doubt some of the most stunning and famous photos ever taken came from the Apollo missions and without them they wouldn’t have had the same public support or iconic stature that they have today and nearly all of the were taken by one make of camera.

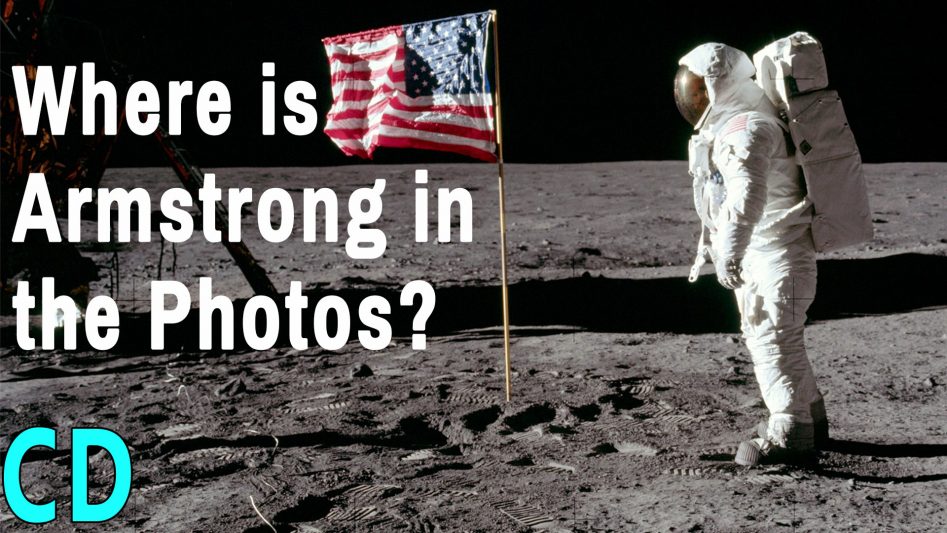

But those pictures weren’t a guaranteed thing, even Earthrise taken by Apollo 8 was a lucky fluke of being in the right place at the right time with the right equipment and on Apollo 11 there is only one moderately average hi-res photos of the first man on the moon Neil Armstrong, outside on the moon.

In the beginning NASA was much more focused on the science and didn’t see much of a need to photograph the journey, so to speak, unless it had a very real scientific benefit. But the photos taken early on the Mercury missions by John Glen with a $40 drug store automatic camera proved they did have a worth beyond that of the purely scientific.

So when NASA started using the Hasselblad 500C, on the suggestion of one of its astronauts, the world got to see space, the moon and the earth in a much better way that is instantly recognisable today. This is how one camera gave us those shots and changed the world we see.

When John Glenn bought a $40 Ansco Autoset camera from his local drug store in Florida in 1962, little did he know that he would start a trend that would lead arguably to the most famous pictures ever taken and many more afterwards.

Glenn was about to become the first American to orbit the earth aboard the Friendship 7 mission on February 20th, 1962 and for whatever reason, maybe to bypass time consuming procurement bureaucracy he wanted to take his own hand held camera to record the journey.

His was not the only stills camera on board, NASA had another Leica camera fitted with quartz lenses and prism to take spectroscopic images of stars. As they were above the limitations of the atmosphere these would be able to capture the full spectrum well into the Ultraviolet range. But that would not take pictures of what Glenn saw out the window of his Mercury capsule.

This wasn’t spur of the moment thing, Glenn couldn’t just smuggle it on board in his back pocket, it went through NASA because they modified it for him by turning the camera upside down and adding a pistol grip, modified film advance lever and shutter paddle so it could be operated with Glenn’s left hand and a new viewfinder on the bottom of the camera which was now the top so he could use it with his visor down if required.

While the images he took were good, the limitations of the $40 camera were apparent and by the summer of 1962 when Walter Schirra, the fifth American in space was getting ready he wanted to up the quality.

Schirra, who was an amateur photographer asked photographers from Life and National Geographic which would be the best camera and they told him to get a Hasselblad 500C, a $500 high-end Swedish import that used 60mm x 60mm format film, almost four times the size of the 35mm in Glenn’s Ansco, that would give a much higher resolution image, had interchangeable Carl Zeiss lens and removable film magazine.

Now this is a completely manual, non-automatic compared to the Ansco and much higher quality but it still required modifying to make it usable space and astronaut proof.

The NASA engineers lightened it by removed the leather covering, reflex mirror, auxiliary shutter and changed the waist viewfinder for a custom side mounted one because they couldn’t look down at it with a spacesuit and helmet on in the tight space of the Mercury capsule. They also removed the film release so it couldn’t be accidentally knocked while floating around the space craft and painted it black to remove reflections from the window of the capsule. The film magazine was remade to hold a commercial 70mm cartridge with 18 feet of film permitting upto 70 exposures instead of the usual 12.

While Schirra’s first flight aboard Mercury Sigma 7 on October 3rd, 1962 was 9 hours long and involved lots of technical evaluation, part of the mission was to take two sets of photos of the earth with the Hasselblad, one of which would use a set of coloured filters in front of the lens to help calibrate the spectral reflectivity of clouds and surface features for future weather satellites.

While there were a few bodged exposures the good ones showed the quality of to be much better than before but it would be the Gemini 4 mission when Ed White became the first American to perform a spacewalk which was captured by commander James McDivitt using the Hasselblad that caught the public’s imagination and showed the power that these high quality photos had as they were shown around the world on the front pages of newspapers and magazines.

Both Mercury and Gemini were the build-up to Apollo and this is where the Hasselblad would truly shine and give us photos that will go down in history as the culmination of the first space race and for the first time show us our place in space.

It wasn’t until Ed white’s spacewalk photos went worldwide that Hasselblad found out themselves by studying the images that NASA were using their cameras, so they got in touch to see if they could help in any way, which of course they could.

Modifications that NASA did became standard features in the new cameras as time went by making them more suitable for use in space straight from the factory. This also encouraged the photographic film makers like Kodak to expand the development of a thin polyester base on which the conventional colour emulsions were applied. This thin film and the elimination of the cartridge allowed up 42 feet of film and 160 colour exposures and 200 black and white exposures per magazine. An electric drive was also added to wind the film on and remove the hand crank which made them easier use.

These became known as the 500EL and used either Zeiss Planar f-2.8/80 mm lens or a Zeiss Sonnar f-5.6/250 mm telephoto lens and were first used on the Apollo 8 mission.

Although the Hasselblad’s were primarily handheld single cameras they were used for other purposes, in particular the four camera cluster used for multispectral photography. Here four Hasselblad’s were used together, three of which used black and white film with a different color filters in front of three of them and the fourth with colour film to act as a control image.

On Apollo 8, a 500EL with an 80mm lens was fixed to the left rendezvous window of the command module and used a timer to take images as regular intervals to document docking and the moons surface.

As they orbited the moon, the earth would rise above the surface but on the first three orbits it had been unseen by the crew.

On the fourth orbit the crew were performing a rotation of the command module with the fixed camera looking down at the surface and taking images very twenty seconds. As they did this, the Earth was rising above the surface and was visible from a side window by Bill Anders who took a shot with the Hasselblad fitted with the 250mm telephoto lens but it had a Black and white magazine attached. Anders he quickly asked Jim Lovell to pass him the colour magazine during which time the earth moved out of view from his window but appeared in the hatch window.

Anders quickly took a couple of colour shots, the first one of which became known as Earthrise and went on to feature on the cover of Time magazine and became the poster shot the for environmental movement and showed the earth as it had never been seen before as the blue marbel in the blackness of space above the monochromatic lunar surface, the only colour in the universe as Anders called it. The image was not planned and happened by chance but again proved the value of taking hi-res images during the mission as and when the moment occurred.

Apollo 11 was to thee mission where the photos would be some of the most influential ever taken so everything had to go right but the Hasselblads had never been used on the vacuum of space where the temperature on the lunar surface could go between 120C in the sun and -65C in the shade.

To cope with this they made a version the 500EL called the Data camera which would be worn by the astronauts when on EVA’s. These had a matte silver coating to reflect the sun’s heat to maintain a more even temperature inside. A Reseau plate was also installed which was made of glass and was fitted to the back of the camera body, extremely close to the film.

These plates had very fine crosses engraved into it to form a precise grid which would be exposed on to the images to provide a means of determining angular distances between objects in the field-of-view because there were no known landmarks with known sizes on the lunar surface.

Each of the plates also had the last two numbers of the cameras serial number engraved into it so the camera and the person that took the image could identified later. You can just see them if the images haven’t been cropped at the centre bottom of the frame.

A new Zeiss lens, a Biogon f-5.6/60 mm was made for NASA. To ensure high quality low distortion images, each one was calibrated to its own camera.

The data cameras were also modified to prevent the build up of static electricity on the film when it was wound on in the camera, something that would normally not be an issue with the humidity of air on earth.

However, in the vacuum of space this could build up cause sparks that would affect the image and possibly a fire in the very high oxygen content atmosphere of the lander, something learnt from the Apollo 1 fire. New lubricant had to be developed because the normal grease would evaporate away in the vacuum and wide temperature swings.

Once Apollo 11 was on the surface Armstrong and Aldrin were told to take as lots of images from inside before they left the lander in case the data cameras failed in the vacuum.

The data cameras were fitted on a bracket on the chest of the astronaut’s space suit which meant they could not look down at the camera. The crew had to be trained how to take pictures by pointing their upper body at the object.

As they cameras didn’t have a light metering, the astronauts set the exposure to 1/250th and the f stop to 5.6 for objects in the shade and f11 for those in the sun. If it was an important shot they would use exposure bracketing, varying the exposures one stop up and/or down from the recommended setting, to ensure a good result.

Although there were two data cameras with colour film in the lander only Neil Armstrong wore his as Buzz Aldrin was busy setting up the experiments which they only had 2-1/2 hours to complete them in.

They did briefly swap but this led to a bit of an embarrassing situation for NASA when they were back on earth and the worlds media were clamouring for high quality images from the moon.

No could find a photo of the first man to step on the moon, Armstrong, on the moon. Eventually they did find one taken by Aldrin but it was of Armstrong standing in the shade of the lander and with is back to the camera which is why all the other shots with the data camera are of Buzz Aldrin. Apparently, Buzz was just too busy and the camera just wasn’t part of the job to think about taking photos, something which was rectified on later missions.

Once the magazine had been used it was fixed to a tether by Armstrong and hosted up by Aldrin into the lander and an unused magazine was lowered back down to Armstrong on the surface. The magazine which had the shots taken on the surface were marked as the S magazines and these were the most important ones.

Once the surface mission was over, they took the magazines and left the cameras behind to save weight.

Back on earth the films were developed using a special technique that decontaminated them in order of when they were taken. This was to make sure there were no errors in the cleaning and chemicals used for the later S magazines which contained then the most valuable film in the world.

However, it was during the process of handling on of these S magazines that Terry Slezak, a photo lab technician became the first human on earth to be contaminated with lunar soil from a magazine that was dropped on the surface by Armstrong when he picked out of the protective bag without wearing gloves although they were working in bio-sealed room.

Armstrong had left a note in the bag saying it had been dropped and was a very important and contained the exposures from the surface.

Slezak said afterwards that he had been working on the magazines with his team for almost 24 hours because of the demand for photos and was very tired. He picked up the bag, opened and pulled out the magazine and noticed it was covered in a dark sparkly soot that felt very abrasive. Someone asked him what that was, and he said its moon dust because that where it’s come from.

At that point everyone else left the room and he had to be stripped and decontaminated but was none the worse for handling the dust afterwards.

The Apollo 11 mission carried four 70MM Hasselblad cameras and returned with 9 magazines of film. They took 1409 exposures during the mission, with 1408 useable images: 857 on black & white film and 551 on colour and an additional 35 exposures were made with the Apollo Lunar Surface Closeup camera as stereo exposures of the lunar soil.

The photos made the astronauts and the mission go down in history and it also boosted the reputation of a small Swedish camera maker to similar astronomical heights from which they never looked back and you can still find classic Hasselblad 500 C’s an EL’s cameras second hand should you want use the camera that photographed the all the moons missions up until Apollo 17.

So, I hope you enjoyed the video and if you did then please thumbs up, share and subscribe.