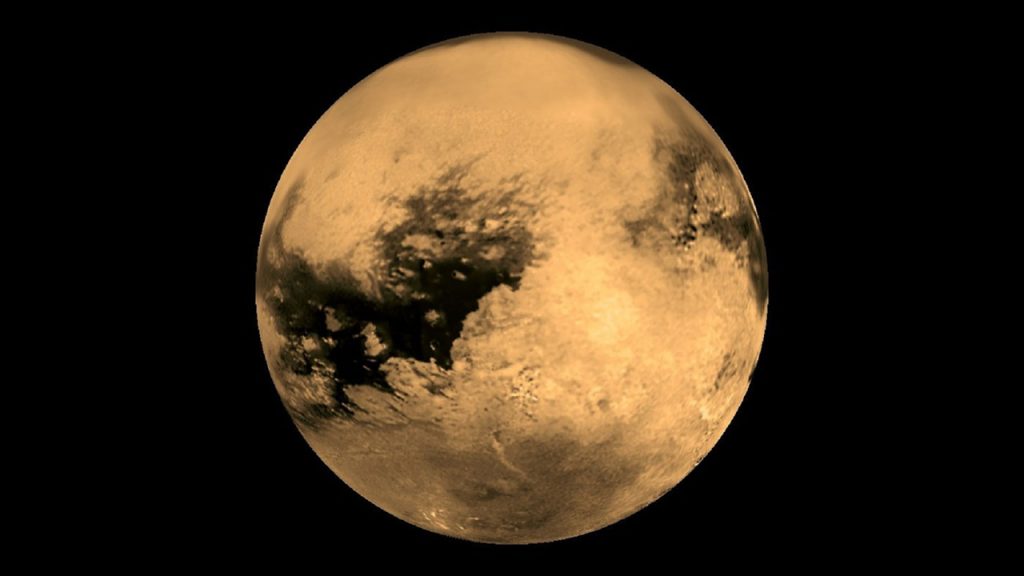

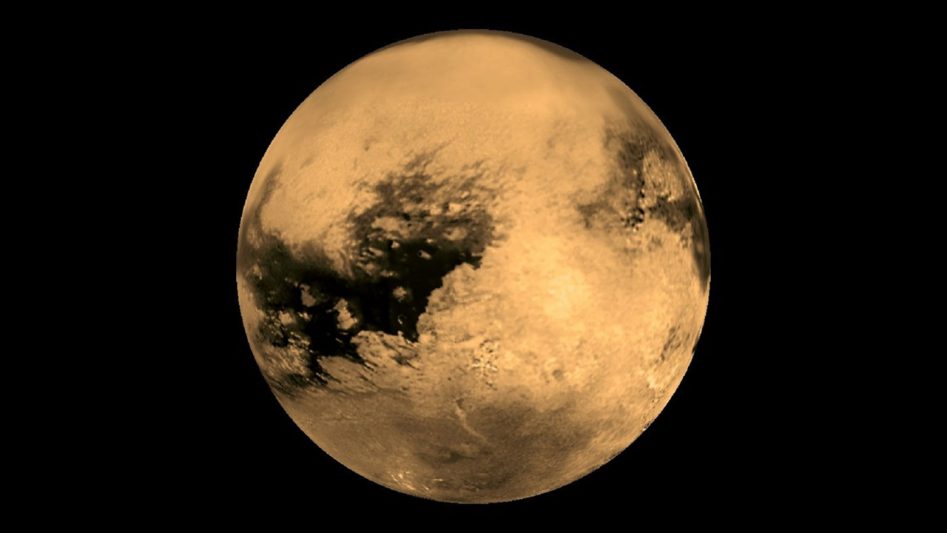

titan

Titan… the largest moon of Saturn. And the second largest moon in the solar system. I use the term “moon” loosely. Technically Titan is a moon, but only because it happens to orbit around an object that is not the Sun. In any other situation, Titan would certainly be categorized as a full-blown planet, beating out Mercury and Pluto in size, and holding the honor of being the only moon in the solar system possessing a thick atmosphere. This makes Titan an interesting and important place for planetary scientists… and those of us who would like to plan vacations on other worlds.

In fact, Titan was considered so important in the 1970’s, that a flyby of the enormous moon was planned for the Voyager missions. Voyager 1, which would reach the Saturnian system first, was scheduled to stray from the planetary plane in an attempt to get a closer look at the elusive moon. This would put Voyager 1 on course to leave the solar system forever, and, should it fail, Voyager 2’s trajectory would have been altered to put it on the same course. Meaning, we would have missed out on Voyager 2’s eventual flyby of Uranus and Neptune. NASA considered Titan to be more important than Uranus and Neptune… now that’s pretty important!

So what exactly does lay below the thick blanket of orange haze that shrouds Titan?

This was one of the many questions at stake when the Cassini-Huygens mission began with an ordinary, uneventful launch on October 15, 1997, lifting off at 4:43 am EST. Of course, the mission was not bound solely for the foggy moon. Despite its mysterious appeal, Titan’s much larger neighbor, Saturn, held some incredible secrets of its own, including a vast and complicated ring system, and a whole slew of other moons to explore. So the majority of the science would involve investigating the entire Saturnian system. But a portion of the mission was dedicated to a fantastic first step in exploration of the outer solar system: The Huygens probe would land on Titan.

Cassini-Huygens was a joint venture between NASA, ESA, and the Italian Space Agency (ASI). The mission objective was to send a spacecraft to explore Saturn and its system including the rings and the moons. The primary vehicle was Cassini, a state-of-the-art spacecraft meant to pass through multiple orbits of the system, photographing and taking measurements along the way.

Backpacking across the solar system along with Cassini was its kid brother, Huygens, whose sole purpose was to detach from Cassini and parachute through the smoggy Titanian atmosphere. The Huygens probe contained six instrument packages, primarily for sending back data about the atmosphere. One package was dedicated to surface instrumentation in the hopes that it would actually make it to the surface, which, at the time, was entirely unknown. The surface texture was anybody’s guess, but hopes were high that Huygens could bring some clarity to that mystery.

All of the science of Huygens had to be bundled into a container just 2.5 meters in diameter and weighing only 318 kg. Once it was strapped onto Cassini, Huygens looked kind of like a big, gold dinner plate… or a turtle shell. The probe was separated into two modules: the Entry Assembly Module, which carried navigation equipment and a heat shield, and the Descent Module, which carried the scientific instrumentation and three separate parachutes that would let it down easily onto the Titanian surface.

The probe could not actually communicate with Earth on its own, rather it sent all data to the Cassini spacecraft, which then relayed it back to Earth. Huygens took 2.5 hours to descend through the thick, smoggy Titanian atmosphere on January 14, 2005. Once it landed on solid ground, (the probe had been designed for a possible “liquid” landing too, just in case) it was able to communicate data to Cassini for over an hour before its batteries died recording a surface temperature of -170 C. That’s pretty cold!

So what did the Huygens probe find? Little green men? Not exactly. In fact, the probe was not designed to look for micro-organisms at all. It’s primary objectives were to gather data about the makeup of Titan’s atmosphere, while snapping some pictures of the surface, both of which it accomplished swimmingly. The probe was not expected to last very long on the surface, but it continued to take pictures and measurements of the temperature, texture, thermal conductivity, heat capacity, and speed of sound at the surface for over an hour.

Huygens provided evidence of rain and weather, albeit in the form of liquid methane and ethane rather than liquid water. It verified that there is, in fact, water on Titan, just not in a liquid state. The surface itself is made of water ice pebbles and rock, as is much of the crust. The probe also detected the presence of a liquid ocean under the crust and multiple small seas of liquid methane on top of the crust. Winds in the atmosphere blew the probe around as it floated down, just as it would have on Earth.

In fact, the place looked shockingly similar to Earth, in a “not the same at all” kind of way. What I mean is, Titan has many of the same features that Earth has, it just exists at a totally different temperature, much colder than Earth. At such a low temperature, elements act wildly different than they do on Earth, yet create features that are surprisingly similar to those found here. Sort of like The Bizarro Earth (Seinfeld fans?)

Does this Bizarro Earth have life on it? Well, not as far as Huygens was able to detect. But let’s take a look at this question from a different angle. What are the odds of actually running into life when dropping a single probe onto the surface of a planet/moon/object in the solar system? Let’s say that the roles are reversed and the little green men dropped a tiny probe onto the surface of the Earth. What would they find?

Odds are good that their probe would land in the ocean, which would almost certainly show no sign of life at initial glance. But for argument’s sake, let’s say they did manage to touchdown on terra firma. The little alien probe would likely not come into contact with any kind of complex life such, as an animal. It is more likely that the probe would encounter a variety of plant, but even if it did, would it recognize a plant as a lifeform? And what if it landed in the middle of the Sahara, or at the top of Mount Everest, or in the middle of Antarctica? A probe could miss complex life completely, depending on where it happened to land and how long it happened to hang around to see what was crawling or blowing around.

Of course, bacteria is present everywhere on our planet. But what if our little green friend doesn’t know bacteria the way we know bacteria? What if life, as we know it, looks nothing like life as he knows it? And what if, like the Huygens, the little probe had no ability to look for bacteria? Then the little green man would mark a big UNKNOWN next to the “Does life exist?” box in his mission checklist and continue about his day. We know that our planet is teeming with life, but with such a brief and limited snapshot, our little alien friend wouldn’t necessarily know that.

So let’s turn the tables back to the original question: What are the odds that humans would send a probe to another object in the solar system and actually observe a complex life form with just a few minutes of measurements and some rudimentary data? Probably pretty slim.

The Huygens probe was one of the most successful spacecraft in history. It wins the prize for the most distant man-made object to make landfall on a foreign body and it did some extraordinary science on its way down. As far as interesting destinations in the solar system, Titan proves to be right up there at the top, much to the credit of Huygens, the little space probe that could.

Perhaps a manned mission one day? That would certainly be interesting. Unlike most everywhere else in the solar system, you wouldn’t need a pressure suit to take a walk on Titan. You’d need thermal controls and oxygen in your spacesuit, but you wouldn’t require a big balloon suit as you would in a vacuum. Otherwise, you would have many of the luxuries you have on Earth: a rocky surface, gravity similar to that on the moon, and sunlight, albeit dim sunlight, but sunlight nonetheless. You’d also have dunes, beaches, oceans, mountains, volcanoes, rain, and weather. If you stayed around long enough, you’d get to experience the seasons, since Titan is one of the few places in the solar system apart from Earth that has them. And when it was time to leave, you could park your spaceship next to the nearest lake, fuel up with methane and blast off for home. Sounds like a pretty cool vacation spot to me!

References:

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/spacecraft/huygens-probe/

https://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/science/titan/

Photo courtesy of NASA

Comments

Loved the article!! Learned alot and for some reason feel like I should be packing my suitcase. ha!