When Rolls Royce went into receivership in 1971, it was like a hammer blow to british industry and was almost as unthinkable as the fall of the monarchy or the Chruch of England, and yet one single project caused more damage than the combined forces Hilter and the Luftwaffe in the darkest days of world war 2 to bring down one of the most famous engineering names in the world.

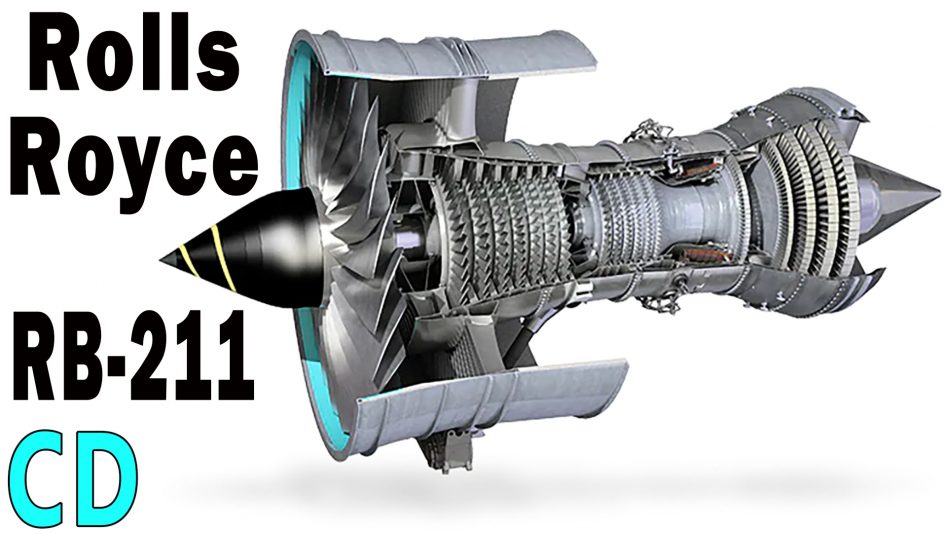

However, in a twist of fate worthy of any great piece of fiction that same project was also the salvation of Rolls Royce and turned it from a mid-sized engine maker into a global leader. This is the story of the RB211 high bypass turbofan.

To find out how Rolls Royce got in to such a position we have to go back a few years to America and the introduction of a new type of large wide-bodied aircraft that airlines were looking to buy which would allow them to move more people more efficiently and over longer distances.

Part of this had been driven by the crossover of military programs like the US defence competition for the Heavy Logistics System which saw the developments from Boeing, Lockheed and Douglas, which went on to create the Lockheed C5- Galaxy and the much more successful loser that became the Boeing 747.

Other new wide-bodied aircraft developed in the late 60’s and driven by demand from the airlines were the Douglas DC10 and the Lockheed L-1011 Tristar, these also required three engines instead of the usual two for redundancy for long flights over water.

With such large aircraft, there was a need for large engines with GE supplying the CF-6, the larger civilian version of the TF39 from the C5 Galaxy and Pratt & Whitney supplying the JT9D developed for the Boeing 747.

Key to these new engines was the newly developed High Bypass Concept which used a much bigger fan. This provided extra thrust by completely encircling and flowing around the outside of the engine core. The large fan also ran at a higher pressure ratio of about 1.5 which acted like a supercharger for the core too.

These new engines needed to be both powerful and lightweight for their size with thrust outputs in the 43,000 lb range.

Rolls wanted a part of this new and expanding market and thought they had an advantage over the others because they had been developing the worlds first 3 spool High Bypass Engines.

In this configuration, 3 sets of turbines spin on three concentric shafts which drive the compressors sections at different speeds, allowing each one to be more efficient than a typical 2 spool engine.

Rolls had also been developing carbon fibre “Hyfil” fan blades, the combination of this and the 3 spool design would give them a greater power to weight ratio than anything on the market.

Rolls developed the first turbofan engine to enter service, the Conway in the early 1950’s and in 1961 they started work on a high bypass engine to replace the Conway. This led to the development of the RB178 but they were in a more difficult position with smaller budgets than their US counterparts.

The development budget for the RB178 being just £2.6 Million compared to the $20 Million development funding that GE and Pratt and Whitney received from the US Dept of Defence.

Instead of designing a finalised engine, rolls developed their engines in stages so there would be varying power outputs up to the specified final product. This continuous development work meant that a large number of people were involved with the project as it went on and at its peak, 770 people worked on the design.

This also created lots of expensive stock and spares which had to be managed and stored as changes to any part could happen at almost anytime during the development process.

The US firms also had much greater running experience with the US airline, something that Rolls normally got with Military contracts and testing programs first but these engines would go straight to the civilian sector. In the UK the RAF didn’t get their first RB211’s until 1983 and they were secondhand ones from British Airways.

Rolls lost out to Pratt and Whitney when Boeing refused to use the RB178 for their Boeing 747. This led the cancellation of the RB178 but in its place they came up with the A.T.E or Advanced Technology Engine family that would go from the RB203 with 10,000 lb thrust to the RB207 at 60,000 lbs of thrust for the Airbus A300.

But another blow came when the UK pulled out of the Airbus programme leading to the cancellation of the RB207 which was dropped in favour of the smaller RB211 and it was this engine that Rolls targeted the Lockheed Tristar with.

Lockheed could see that the RB211 would be a superior engine and give them the edge over the very similar Douglas DC-10. In 1968 Rolls agreed on a performance guarantee with Lockheed that the new engine would be delivered by September 1971 and would produce a stated 42,000 lb thrust even though the new engine only existed on paper and they knew the issues around launching a new engine with untried technology.

Rolls soon found themselves in a difficult position, everything about the RB211 was bigger than they had ever dealt with before, the fan was over 7ft or 2.1M across, as were the casings and rings on an equally large size. The operating temperatures and pressures were also higher than anything they had done before.

One of the main features of this engine was the Carbon-fibre Hyfil fan blades, these would be considerably lighter than titanium ones, this also translated into a lighter hub, bearings and frame. But this new technology had cost a huge amount of money not only to develop but also to make the tooling for mass production.

In tests, the new blades worked well but when it came to the obligatory birdstrike test, when 4lb chickens from the local supermarket were fired at high speed into the blades at takeoff speed, the resin on the thin leading edge of the blades failed.

In a stroke, the power to weight ratio advantage against the competition that the Hyfil blades gave was wiped out and so was the time and money that had been invested.

As a fall back, Rolls had also developed titanium blades for such an eventuality but even here there here problems. The Derby factory where the RB211 was being developed had pioneered air-cooled turbine blades for the Conway bypass jet in the mid 1950’s.

These were forged from nimonic high nickel alloys which would keep most of their strength up to 900C. In the Conway peak gas temperature was 1100C so the cooling holes would need to keep them 200C cooler than the surrounding gas but in the RB211 the gas temperature would be 1250C, which at first doesn’t look much of an increase but the strength of the blade decreased by 25% for each 25C over 1100C.

Making the blades was also very costly and an engineers nightmare. Each blade would be made from a rough bar which then had many small but long cooling holes drilled in them. This rough blank would then be heated till it was white hot and the squeezed between two dies to achieve the final shape.

They would then be machined to the precisely correct size and profile but microscopic variations in the cooling hole size between different blades would cause uneven cooling.

At Bristol Siddeley, they had stopped making forged blades in 1960 in favour of cast ones using materials that were stronger than nimonics and too hard to be forged or machined. They could produce blades with mirror finish that only required machining of the root using lost wax casting , a technique for making precision casts that dates back thousands of years.

This is where the top engineers come in, these highly skilled people sometimes moved from one company to another and were in great demand like Stanley Hooker. Hooker had started at Rolls in 1938 and worked on all of the major Rolls engines of the war. He then went to Bristol Siddeley before retiring but he was coaxed out of retirement when Rolls bought out Bristol Siddeley to help sort out the RB211.

However, things at Rolls were about to get a lot worse, the 3 spool design had problems with oil leaks and bearing failures but it was when the RB211 was first run they came into sharp focus. The performance was way down on from what it was expected to be coming in at just 34,000lb thrust instead of the guaranteed 42,000.

When Hooker looked at the engine he found that the HP turbine efficiency was very low at 65% and the speed of the three spools was way off the design values. These are things that should not been allowed to happen but in 1967 Rolls had lost one of the best troubleshooting engineers in the world with the death of Alan Lombard, without his leadership the project was coming apart at the seams.

Development costs had doubled to £170M from the original estimate and the cost of making each engine was more than their sale price of £230,000.

Hooker set to work at fixing the issues and within a matter of weeks had not only regained the missing performance but been able to go way beyond it.

In February 1971 just before the engine could be put on test, the shock announcement came that Rolls Royce was insolvent. After years of huge outgoings on the RB211 and no sales because of delays, it had broken the company.

As Stanley Hooker said, for once the British government moved at lightning speed to buy Rolls Royce overnight before the creditors could claim its assets and because of it’s strategic importance but they wouldn’t buy the RB211 and neither would anyone else but the engine itself well on its way to achieving its stated performance and more.

Lockheeds boss, Dan Haughton, who had refused to change the contact before to help out Rolls was now in a bad situation himself because if they couldn’t get the engines, the Tristar project and Lockheed itself was in danger of collapsing.

The UK government put pressure on the US government to guarantee bank loans to Lockheed to keep it from going bust. A new contract with Lockheed was negotiated with the penalties for late delivery dropped and the price per engine went up by £110,000 each

Hooker was appointed technical Director and brought in a team of retired engineers from Rolls Royces past including Cyril Lovesey and Arthur Rubbra both of whom were over 70 to use their vast experience which dated back to the Merlin days to make the RB211 reliable and producible in numbers and keep the cost under control.

Hooker was also given the power to bring in the best engineers as he saw fit from other engine projects which totally transformed the RB211 program.

The first RB211 was certified on April 14th 1972 and the first Tristar entered service on April 26th 1972, the initial engines still had teething issues but within a few years a programme of mods made things much better and the engine became highly reliable.