Earlier this year, Professor Stephen Hawking warned the human race that, unless we found a way to colonise another planet in the next hundred years, we would face a very real threat of extinction. He said: “With climate change, overdue asteroid strikes, epidemics and population growth, our own planet is increasingly precarious.”

The idea of a brave band of people leaving Earth to start a new life elsewhere in the galaxy isn’t new. Rocket pioneer Robert H Goddard described an “interstellar ark” in 1918, and ten years later his Russian counterpart Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, known as the father of astronautic theory, wrote about a Noah’s Ark that would fly in space for thousands of years.

But there are a stack of seemingly insurmountable problems to building a ship like that. With the exception of the moon and Mars, we still don’t know where it might go, and it’s also likely that the construction process would involve the kind of international teamwork that seems impossible in today’s political environment.

But those issues aside, what are the main problems facing the crew of a space ark? The first is how to keep it moving. Where will its engines get their energy from?

In the 1950s, Project Orion – not to be confused with NASA’s Orion space programme – explored the idea of powering a vehicle by detonating atomic bombs at its rear. The explosions would be so powerful that they’d take place outside the craft because they’d destroy it if they took place inside. Model test flights began to be flown in 1959.

The Project Orion concept was taken further by the British Interplanetary Society, who started Project Daedalus in 1973. But it wasn’t strictly a space ark concept. Instead, the aim was to send an unmanned spacecraft to a nearby star within a human lifetime. The target was Barnard’s Star, 5.9 light years away, to be reached during a 50-year flight. Since 1998, Pennsylvania State University has continued Orion-based experiments.

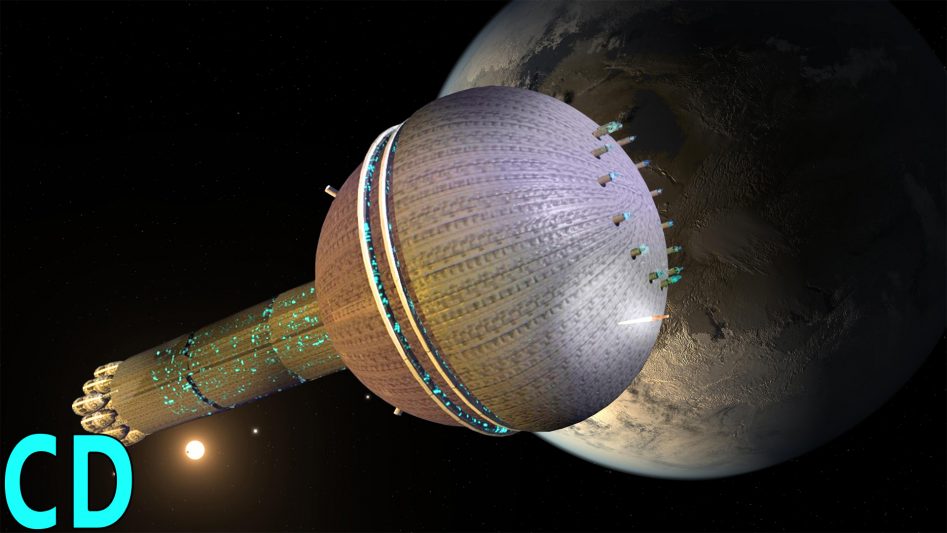

Dr Robert Enzmann proposed his Enzmann Starship in 1964. It would be fuelled by a frozen sphere of deuterium, a million tons in weight, with a cylinder more than 500 metres long attached behind it. The deuterium would power a set of nuclear fusion rockets, with three 90-metre living compartments capable of containing more than 200 people.

While propulsion is still under research, the next problem is reliability. With no one in the emptiness of space able to help, and turning back not being an option, an interstellar vehicle would have to be incredibly reliable, because the crew would have to make any repairs with what they had aboard – or die in the attempt. Any vehicle carrying the future of humanity to a new destiny will need to be almost infallible.

But there’s an even bigger problem – keeping the crew healthy, happy and focused. Anthropologist John Moore suggested in 2002 that a crew of around 160 would be enough to offer sufficient biological diversity and a secure future for the human race beyond Earth. But Cameron M Smith calculated in 2013 that, if accidents and disease are taken into consideration, several thousand people might need to be aboard the one-way flight.

Regardless of how many there are, they’re all going to face issues that no one has ever faced before. And that’s true whether the space ark is a sleeper ship, with everyone aboard in suspended animation, or a living ship with the crew awake and working.

They’ll know that going home is not an option, and wherever they end up will have to become home. They’ll experience a different type of social development from what happens on Earth, and no one can say how it might turn out.

Spare a thought for the crew of a generation ship – those who leave Earth know they’ll die before the journey is over. But the generations born during the flight won’t have a home planet, and they’ll live with the knowledge that they’re only there to make life better for people in the future. Imagine telling your children that – the teenage sex talk is easy in comparison.

There’s also the horrifying concept of advances in technology meaning that a better, faster ark is launched after the first one, and reaches the target planet sooner – so that the first crew, having spent 200 years in flight, arrive to find a human colony has been there for a century already.

The question of how to keep the peace is also a difficult one. The crew would have to become a self-policing community. How could that be enforced? Moore argued that family units have been more successful than military units in colonisations of the past, citing the example of the Polynesians, who sent young couples off in boats to find new islands where their children would be born on, effectively, a new world. But imagine a family Christmas argument that spreads to involve every member of an ark crew, in the middle of nowhere with no one to mediate?

There have been a number of human experiments, which have yielded various results. In 2016 NASA completed a year-long isolation experiment involving three men and three women, who were locked in a 36-foot diameter dome. NASA said the results proved a mission to Mars was achievable in human terms – while the participants reported that boredom was the biggest enemy, and their advice to others was: bring lots of books. But that was just a year and on earth with the participants knowing its just a test that could be ended in an emergency.

The real thing would bring physiological issues which would have to be planned for well for in advance with people that can get along with each other, the last thing you need is people wanting to kill each other by the end of the journey or before. At the fastest current estimated speed of about 5% the speed of light, Mars is nine months away – but the nearest star, Alpha Centauri is 88 years away, and the centre of the Milky Way galaxy, however, is 600,000 years away.

There’s yet another issue. if all goes well, there’s no epidemic or some other disease problem, the space ark is completely reliable and the crew remain focused on their mission, there’s the additional possibility of human evolution continuing – and taking an unexpected turn. Perhaps, a long time after leaving Earth, the people who arrive on New Earth will be nothing like us at all. So… does that mean the human race as we know it will have really survived?

Thanks for watching and this episode’s shirt was the Tabla Paisley by Madcap England and is available from www.atomretro.com/madcap_england with worldwide shipping from here in the UK.